Honouring the voices of the institutionalized

University researcher’s book explores patterns of violence in facilities intended to provide care

November 11, 2018

In a recently published book, University of Ontario Institute of Technology Legal Studies researcher Jen Rinaldi, PhD, proposes that the same facilities designed to deliver care to vulnerable populations instead encourage a culture of violence and dehumanization.

Learning from the experiences of Huronia Regional Centre survivors

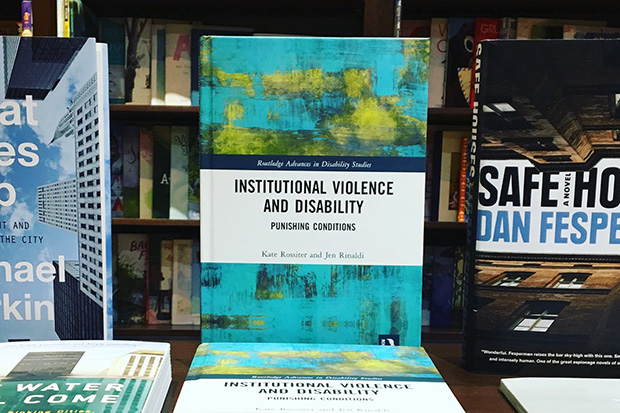

Dr. Rinaldi, an Assistant Professor in the university’s Faculty of Social Science and Humanities, co-authored Institutional Violence and Disability: Punishing Conditions with Kate Rossiter, PhD, Associate Professor in Health Studies at Wilfrid Laurier University. The book explores the pervasiveness of institutional violence through the lens of survivors of the Huronia Regional Centre (HRC) in Orillia, Ontario.

HRC was an institution for children with diagnoses of developmental disabilities operated by the Government of Ontario from 1876 to 2009. It was an isolated and enclosed establishment, designed to control most aspects of its residents’ lives, all in the name of efficiency. These control measures were used to justify the torture and neglect of residents.

The HRC was the subject of a class action lawsuit survivors brought against the province for abuse endured while institutionalized. The case resulted in a $35 million settlement and other non-monetary gains, including a public apology delivered by then-Premier Kathleen Wynne.

Exploring the effects of institutionalization

Dr. Rinaldi’s and Dr. Rossiter’s book compiles more than four years of research. By interviewing and analyzing the experiences of HRC survivors, they explored:

- How the conditions in institutional settings produce violence and entrench violence as a cultural norm.

- How institutional violence has been justified by staff and reproduced in a community.

- How survivors experience and resist legacies of institutional violence.

The researchers discovered that within institutional settings, violence was not an aberration, but rather an ordinary everyday expectation.

"Residents were publicly humiliated, beaten, put in solitary confinement and sexually abused," says Dr. Rinaldi. "The models of care themselves justified violence and made violence possible. We concluded the violence experienced at the HRC was not the result of a few ‘bad apples.’ In fact, there is no way to ‘do institutionalization right’. Institutionalization in and of itself constitutes a culture of violence."

Listening to the survivors’ stories is difficult but necessary if society is going to learn from the past.

"The resilience of the survivors is remarkable," says Dr. Rinaldi. "The stories they shared have been weighty, shocking and profoundly sad. I marvel at the survivors’ capacity to persist and to self-advocate. It is an awful thing to know a population has experienced a collective trauma, one that continues to permeate all they experience and do. Yet this trauma continues to receive little public acknowledgment and remediation. I suppose our largest challenge was holding these stories and doing them justice: bearing witness in a way survivors deserve and expect."

Lessons for future generations

As other stories of abuse and neglect have surfaced over the years, the institutional approach to caring for vulnerable populations has become less commonplace and acceptable in Canadian society. However, Dr. Rinaldi points out similar models of institutionalized control continue to be enforced. The incarcerated groups today may be different, but the pattern of violence is the same.

For example, throughout 2018 migrant youth from Central America have been removed from their families at the U.S.-Mexico border and kept in state-run facilities. In a Globe and Mail opinion piece, Dr. Rinaldi and Dr. Rossiter argued these new forms of institutionalization have the potential to produce the same patterns of violence as those experienced at HRC, because the organizational structure is similar. Daily violations and humiliations lead to violence, especially when the incarcerated are culturally devalued and socially invisible.