University researcher’s findings could help save the life of your pet

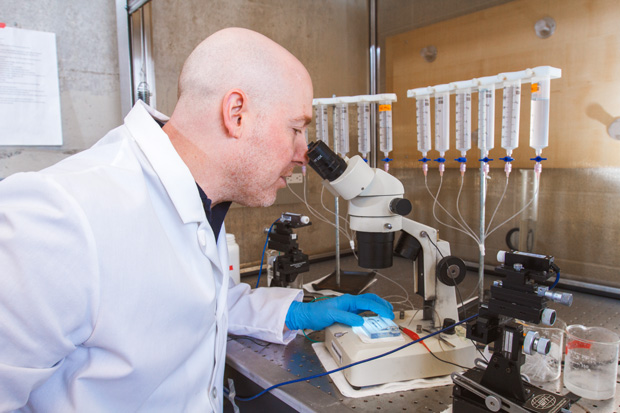

Sean Forrester, PhD exploring new approaches to prevent heartworm in dogs and cats

June 22, 2018

University of Ontario Institute of Technology researcher Sean Forrester, PhD and two U.S. counterparts hope their scientific work will break new ground in the prevention of heartworm, a potentially fatal disease in dogs and cats.

Primarily transmitted to mammals through the bite of an infected mosquito, parasitic heartworm larvae migrate to the vessels of the heart and can impact various organs in the body.

Dogs in particular are natural hosts for heartworm. Worms as long as 30 centimetres (one foot) can develop within six months, and live for up to seven years inside the animal. Once present, heartworm can be costly and difficult to cure.

Dr. Forrester, along with research groups at the University of Georgia and the University of Wisconsin-Madison are receiving new research funding (US$200,000) from Kalamazoo, Michigan-based animal health company Zoetis to study the disease.

“Heartworm can be prevented by treatment with anti-parasitic drugs, also called anthelmintics or nematocides,” says Dr. Forrester, a parasitologist and Associate Professor of Biology in the university’s Faculty of Science, “However, parasitic nematodes are notorious for becoming resistant to current treatments. That’s why we need new research into novel therapeutics.”

Dr. Forrester's research program at the university focuses on understanding the function of neurotransmitter receptors in parasitic nematodes and their potential as drug targets.

“We were impressed with the calibre of the innovative research proposals we received, and we selected three proposals that will augment our internal research and development and could possibly lead to new scientific insights in parasitic disease, in particular, heartworm disease,” says Dr. Debra Woods, Research Director, Head of Parasitology Global Therapeutics Research, Zoetis. “New therapies will likely be required as heartworm resistance to current therapies develops over time.”

Helpful links for more information:

- Canadian Guidelines for the Treatment of Parasites in Dogs and Cats [PDF]

- Heartworm Basics (American Heartworm Society)

Media contact

Bryan Oliver

Communications and Marketing

Ontario Tech University

905.721.8668 ext. 6709

289. 928.3653

bryan.oliver@uoit.ca